Sometimes you read an article or blog post by another teacher and think, ‘Yes! Thank goodness somebody else thinks that too!’ That was the case this week when I read a post by Emma Turner called ‘Powerpoint and IWBs – It’s time to reclaim analogue teaching’.

Turner, a highly experienced teacher, school leader and education consultant, makes a passionate and well-argued case for a return to ‘the beauty and effectiveness of analogue teaching’, in an era when the default seems to be for students to spend large chunks of lesson time passively watching pre-prepared slides on a giant screen, which has, she argues, ‘assumed a shrine-like status in our classrooms’. It’s well worth reading the whole post, but my favourite paragraph is this one:

Teaching is about responding to the emerging thinking in front of us. It is not about producing neat, sanitised sequences for passive recipients to be presented with. Teaching is alive, it is interrogative, it is dynamic; it is fizzing with variables and influences, so the very idea that a route through a challenging concept with 30 individuals all with unique schema and experience can be predicted and planned for with any degree of invariability is bordering on farcical.

Turner’s case for ‘analogue teaching’ is applicable to all subjects and all ages, but as an English teacher that phrase ‘fizzing with variables and influences’ particularly resonates with me.

It’s been lovely to see the response to Emma Turner’s blog post, with other teachers chipping in with their lists of tried and tested classroom ideas which don’t involve screens and slides, and which, instead, call for pipe-cleaners, plasticine, shoe-boxes, crayons, sugar paper, props, costumes, sock puppets, old rolls of wallpaper and so on. Or which, in English lessons, simply involve reading aloud, without recourse to pre-prepared notes on slides, and then getting students to write creatively in response.

One of the lessons I most enjoyed teaching last term came at the end of a Year 8 unit on poetry. It was the last week before Easter and I’d taught all the poems in the scheme of work, plus a couple of extras. I was looking for something to sum up our sense of the range of poems we’d been exploring together, and also to leave my students with a memory of poetry as being something playful, and, above all, something that they could access and enjoy with confidence.

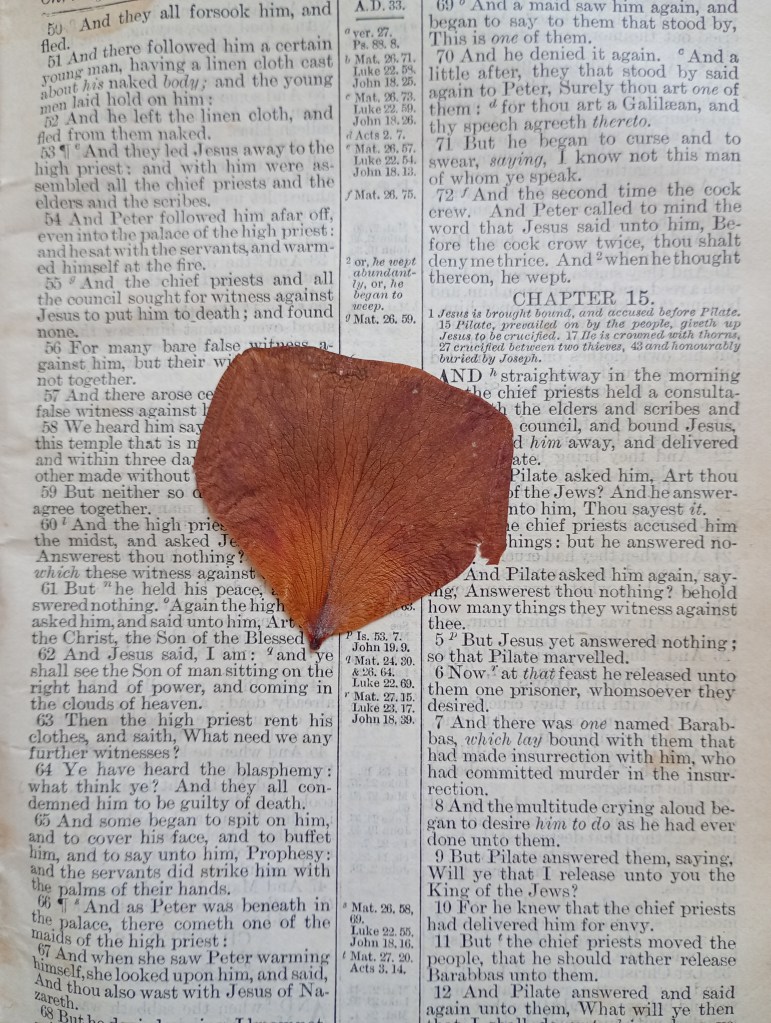

Like many of the best lessons, this one was easy to set up, and involved very little input from me during the lesson itself. All I did was to copy and paste four of the poems we’d studied, without their line breaks, into a Word document, leaving 1.5 spacing between the lines. I printed one sheet for each student in the class. And then I gathered all the scrap paper and cardboard I could find: the lids of old boxes lying around in the English office; the sheets of cardboard that often come in packs of A4 lined paper; flaps of old document folders that had been used many times; scraps of sugar paper; offcuts of coloured card.I brought all of this to the lesson, together with as many glue sticks and pairs of scissors as I could find. The lesson wasn’t entirely Powerpoint-free: I had one slide with an example of a cut-out poem on, just to give students an idea of what sort of thing they would be creating.

That was it. For a whole hour, on a Wednesday afternoon, my students were busily, happily and, best of all, creatively engaged in selecting, snipping, placing, rearranging, hunting, editing, adapting, illustrating, explaining as they created their own cut-out poems, using words from the poems we had been studying in our previous lessons. It was one of those lessons when, for much of the time, I really needn’t have been in the room at all. That freed me up to circulate and chat to students as they worked, hearing about the creative challenges they were encountering and how they were solving them. For example, what to do if you really needed a particular word and it wasn’t there? One student painstakingly snipped out every letter to spell the word he needed. Another did the same, and then realised that this meant she could be playful about the spacing between the letters, deliberately stretching the word out. She was able to articulate with great confidence why she had decided to do this and what impact she intended it to have on the reader.

At a time when there is so much concern about the amount of time young people are spending online, it was so heartening to see how satisfying these Year 8 students found the physicality of cutting, arranging and sticking, and how proud they were of what they produced.

In a lesson like this it’s amazing to see how everyone starts with exactly the same text – the words from four of the poems that we’d studied – but by the end of the lesson no two poems are alike. Cut-out poetry is an approach that supports those who lack confidence in writing: no one need worry about staring at a blank page, because the starting-point is always a page full of words. But it allows for huge flexibility in response. To return to that quotation from Emma Turner’s blog, it’s an approach that is ‘alive, it is interrogative, it is dynamic; it is fizzing with variables and influences’.

I welcome the sharing of approaches that celebrate what happens in classrooms when students are given the space, resources and inspiration to be active creators, rather than passive recipients.